Central Bank Digital Currencies and Libra in the Spotlight

by Matthew Allen, SWI swissinfo.ch February 7, 2020It appears that central banks are devising a response to decentralised money, such as bitcoin – by contemplating new centralised digital versions of their own currencies. This goes by the name of Central Bank Digital Currency, or CBDC.

Libra’s stablecoin project launched in Geneva last year was a “watershed” moment that “kicked everyone in the pants”, Michael Sung, a professor at Fudan University, told the Crypto Finance Conference (CfC) in St Moritz last month.

This prompted China to “massively accelerate” its drive to digitize the renminbi. Sung is convinced that the plan is to spread the RMB far from China’s borders and “increase adoption throughout the world.”

On the fringes of CfC I chatted to Aleksander Berentsen, a professor of finance at the University of Basel. He speculates that the Chinese central bank may one day open its doors to commercial banks in regions such as Africa and South America, allowing them to funnel digital RMB cross-border for their own companies and consumers to use.

This might compel other countries, particularly the United States, to respond in kind, prompting a potential flood of CBDCs for the public to get their teeth into. But the Swiss National Bank (SNB) would want none of this. It would only contemplate “printing” a digital franc for professional traders.

The SNB fears that creating a general public digital franc would divert its attention away from its main purpose of maintaining price stability. It also fears the consequences for high street banks. Who would hold a commercial bank account, particularly in times of economic stress, when they have the safer option of an SNB account?

And if people stop depositing their pay cheques at commercial banks, bang goes their revenue stream of lending customer money to others, whilst charging more interest on loans than they pay out on deposits.

So much for the theory, but what are CBDCs? Central banks “print” digital money all the time, which form their reserves. The SNB uses this money to buy financial instruments in other currencies, for example using francs to buy euro-denominated bonds. This is to keep the franc from appreciating too much in too short a time span.

The new form of CBDCs could be used for a variety of purposes: to internationalise the RMB, replace physical cash in countries like Sweden where there is declining public demand for bank notes and coins, provide a means of payment in Distributed Ledger Technology financial systems (such as the SDX digital assets exchange being built in Switzerland), or to grant basic banking services for people in countries with a weak commercial banking infrastructure.

Another advantage for the authorities is that they could better monitor who is paying what to whom than they currently can with physical cash.

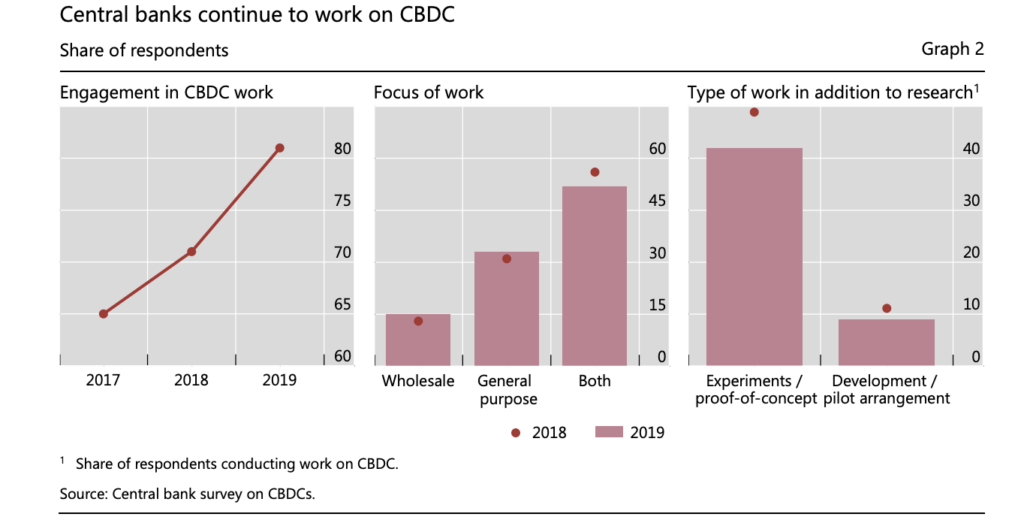

A recent survey by the Bank for International Settlements (a kind of central bankers’ club) says that 80% of members are actively exploring CBDC strategies. Only 10% say they might launch a publicly available CBDC in the near future, and these are all central banks from developing economies.

So where does this leave bitcoin and other digital payment tokens, including private stablecoins that peg their value to traditional cash or other assets? CBDCs may be digital-only currencies, but they would be highly centralised and have no need to operate on blockchain. So they have a different value proposition.

On paper, bitcoin has nothing to fear from CBDC “competition”. So far, public enthusiasm for decentralised money has been limited to a niche set of players. At the end of the day, the future of money will depend on what people actually want.